When working remotely trust within in a new team isn’t something that builds up naturally: Here are some research results and hands-on advice on how to foster swift trust in virtual teams and achieve better project communication and results.

Trust is saving time and money

Research shows the success of a team heavily depends on trusting relationships between team members (e.g. Jarvenpaa/Knoll/Leidner 1998 1; Gilson/Maynard/Young 2015 2) - meaning those teams are more proactive, more focused and provide better feedback (Clark/ Clark/Crossley 2010 3). Team members have to trust one another, the team leader and also the organization they work in to be productive. Trust here is defined as „an individual’s willingness to be vulnerable to the actions of another person.” (Mayer/Davis/Schoorman 1995, S. 710 4).

Trust seems to be even more important if it comes to semi-remote, remote and/or agile teams, where you cannot actually watch your team members work.

How people build trust

The ease of team members building trust depends on individual and organizational criteria: First of all building trust is a matter of ones personality type – some people are more trusting then others. Others are using stereotypes to conclude trustworthiness. Still others watch closely how new people around them act before they build up trust.

Above all, trust is built

- when people meet in person (Snow/Snell/Davison 1996 5)

- after frequent (and successful) interactions (McAllister 1995 6)

- when employees have the opportunity to directly observe what others do (Aubert/Kelsey 20037)

Obviously this makes virtual teams trust-killers: You don’t meet and observing your team members work directly is a real struggle. Therefore, building (swift) trust in remote teams is a task that needs time and attention.

Do‘s and Don‘ts for building trust

Do: Take care of initial interactions that help bonding

Swift trust is established at the phase of the team formation through initial interactions (Clark et al. 2010). At this stage, when trust has only been started to be built, the first impression is telling: i.e. how fast is information flowing between team members? Small hints are (over-)interpreted: e.g. How long does it take to get an email reply from my colleague? Technology but also communication rules can help, as stated below.

Do: Provide best-in-class technology

Since virtual teams absolutely need to rely on technology-mediated communication, one success factor of remote teams is to provide the team with the most supportive technological infrastructure. We have all had the email not reaching its intentional goal or the call cancelled because of bad connection. Technology has to be safe, rich (capable of more than only text) and reliable. Make sure that technology used is seemlessly compatible among the team members (Ford et al. 2017 8).

Do: Provide roles and rules of communication

Unclear roles and rules of communication lead to misunderstandings and hinder trust building. E.g. when team members need to wait for days to get login-credentials and still don‘t see all necessary info, trust – to the team as well as the organization – is not fostered. Therefore establish and use communication rules like a maximum response time. Also make a backup plan for inevitable failures of preferred communication tools - there comes a moment when a tool fails. For remote teams, that means communication breakdown!

Don’t: Build semi-remote teams

Local members of semi-virtual teams report much more positive perceptions of their local than their remote members, while perception is similar in fully traditional or fully virtual teams. We can draw implications for practice here, such as the avoidance of semi-virtual teams whenever possible and the development of strong team identities (Webster/Wong, 2008 9)

This is, because a „team“ of co-located and virtual team members form sub-groups, which according to Burke and Aytes (2002, p. 39 10) leads to group-within-a-group behaviour, i.e. lower interaction of local with remote team-members, resulting in higher conflicts and lower communication and satisfaction (Axtell et al. 2004 11).

A simple example: The co-located members of the team discussed solutions first-handedly and presented them to remote members only later on. The effect was that these solutions were turned down more often than between co-located teams. So semi-remote teams should be avoided. If that is not possible, take the time to let informal communication happen (see tipps below), also bring the team together in person as often as possible esp. at the beginning.

Do: Put emphasis on getting to know each other as human individuals

Onboarding is crucial to new team members – this is true for co-local teams and virtual teams.

Ford et al. (2017) 8 state that an onboarding process for remote teams should include information about team members and their personal background, working style and idiosyncrasies – all information that „face-to-face team members typically acquire informally and that create a sense of familiarity with other members.“

While information about professional qualifications or the role in the team seems to be useful and feasible, trying to grasp work style and personal backgrounds obviously could fail miserably. An explicit „dossier“ about the morning grouches in your team might not create a trustful athmosphere…

The better option is to include opportunities for informal contact with each team member so people can build relationships.

The following two games I recently tried can help provide a setting where people get to know the person behind the role:

Getting to know each other – remote

The „Show your Homescreen“-Game

Why use it?

Everyone lives with and through his or her smartphone everyday. Get a quick clue what matters to your team members in every day life.

How does it work?

Easy as pie: Let your team members upload a screenshot of their smartphone (or Desktop) homescreen e.g. via Padlet.com or in your company’s chat tool. Next every team member shows his screen and tells the others about the 3-4 most used or most important apps in their daily life. You quickly get to know: Does my co-worker travel a lot, does he or she work out (Fitnesstrackers…), read the news or go hiking …

For whom?

Teams up to 10 people, it takes 2-3 min per Person

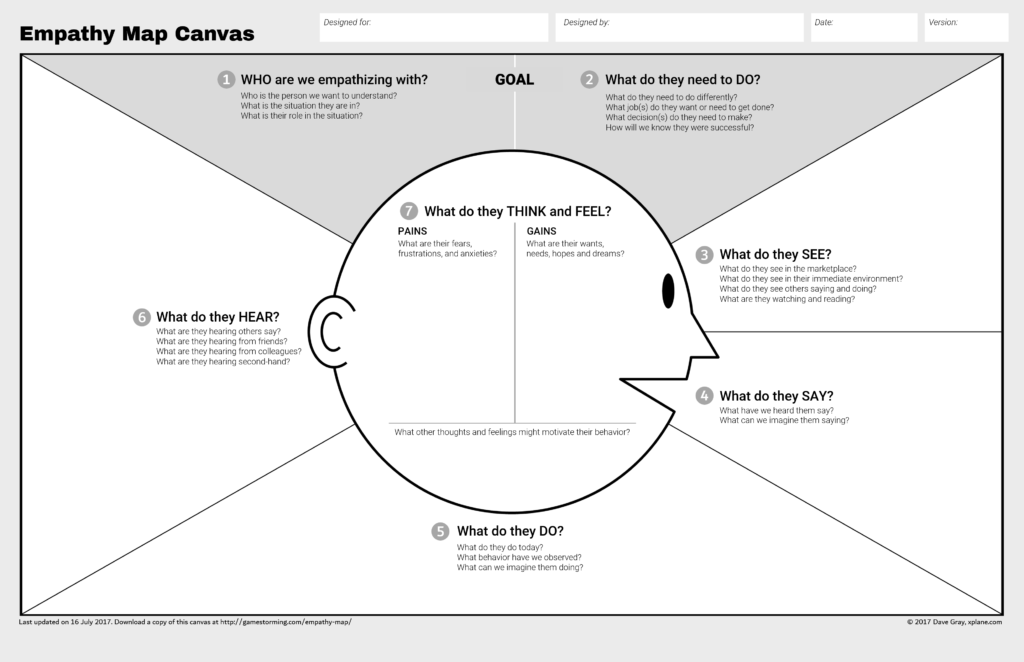

The Empathy Map – of your team

From my personal experience, this one was a real eye-opener: How do our colleagues see you, your role and what you do? I was heavily convinced my co-workers were bored by the tasks we worked on at that time of the project. It came out they weren‘t, but still they wanted to know the larger perspective on why we do certain tasks or follow certain strategies.

The Empathy Map is taken from the great book „Game storming“ (Gray/Brown 2011 12). Though it is originally used to create customer profiles, we used it once in a team workshop to put ourselves in the perspective of a colleague from another work area and get to know their challenges and needs.

Why use it?

With multi-skilled teams from different work areas like Development, IT-Infrastructure, UX/UI, Product Owner and Editorial Board all of these groups have different views and different stakeholders – which they hardly know about

How to do it?

Seperate team members into groups with people from the same work areas – e.g. group all Devs together. Now take a look at the Empathy Map and reflect on your co-workers in that group:

What do they see in their normal work environment? This could mean real entities like buildings, screens but also their bosses‘ face behind a glass door or also „no-one except their two group members.“

What do they say? What phrases are commonly used? E.g. „We are deploying today.“ Or „Of course we can do that.“ „I need more specification to build that.“ Etc.

What do they hear? Sentences that describe the messages they get like „Can you alter that by the end of the day?“ „Does it really take that long?“

What do they feel like during work? Bored? Exhausted? Overwhelmed? Like Super-Heroes? What do they do? Code? Discuss? Design wireframes? List what you think and also, what takes the most time!

Now present the results to the group you reflected on – do so first, without interruptions from the intended group and discuss later. Were you close or totally wrong with your assumptions? What are the challenges for you all as a team? People often have no real clue which tasks their coworkers have in daily worklife.

For whom?

Heterogene Teams, up to 4 different groups

Empathy Map Canvas (source: Updated Empathy Map Canvas)

Further information

Related items

Sources

Jarvenpaa, S. L., Knoll, K., Leidner, D. E. (1998). Is anybody out there? Antecedents of trust in global virtual teams. In: Journal of Management Information Systems, (14) S. 29-64. ↩︎

Gilson, L. L.; Maynard, M. T.; Young, N. C. J.; Vartiainen, M.; Hakonen, M. (2014): Virtual teams research: 10 years, 10 themes, and 10 opportunities In: Journal of Management. 41 (5). S.1313-1337 ↩︎

Clark, W. R.; Clark, L. A.; Crossley K. (2010): Developing multidimensional trust without touch in virtual teams. In: Marketing Management Journal. (20) S. 177-193. ↩︎

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integration model of organizational trust. In: Academy of Management Review, (20) S. 709-729. ↩︎

Snow, C. C., Snell, S. A., & Davison, S. C. (1996). Use transnational teams to globalize your company. Organizational Dynamics, 24(4), 50–67 ↩︎

McAllister, D. (1995): Affect- and Cognition-Based Trust Formations for Interpersonal Cooperation in Organizations. In: The Academy of Management Journal, 38(1). S. 24-59 ↩︎

Aubert, B. A.; Kelsey, B. L. (2003): Further understanding of trust and performance in virtual teams. In: Small Group Research. Vol. 34, S. 575-618. ↩︎

Ford, R.; Piccolo, R.; Ford, L. (2017): Strategies for building effective virtual teams: Trust is key. In: Business Horizons, 60 (1), January–February 2017. S. 25-34 ↩︎

Webster, J., Wong, W. (2017): Comparing traditional and virtual group forms: identity, communication and trust in naturally occurring project teams. In: The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 19(1). S. 41–62 ↩︎

Burke, K., and Aytes, K. (2002): Do Media Really Affect Perceptions and Procedural Structuring Among Partially-distributed Groups? In: Journal of Systems & Information Technology, 5(1) Special edn. S. 33–58. ↩︎

Axtell, C.M., Fleck, S.J., and Turner, N. (2004): Virtual Teams: Collaborating across Distance. In: International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, (9). S. 205–248. ↩︎

Gray, D.; Brown S. (2011): Game Storming. A playbook for innovators, rulebreakers and change makers. O’Reilly. ↩︎